Gilisoft USB Encryption v10.0.0 is a popular product that is marketed as a USB/flash drive encryption solution. It appears to be a continuation of the now discontinued Wondershare USB Drive Encryption product. According to Gilisoft's product description, it claims to be using AES-256 on-the-fly encryption to secure your files. However, after diving into the methodologies employed by this application, as well as the former Wondershare USB Drive Encryption product, I came to discover that no actual file encryption occurs, making the aforementioned statement a blatant lie. Furthermore, your password is stored as plain text along side of your unencrypted files in the application's hidden data store(NTFS Alternate Data Stream) on the NTFS file system.

In this short article, I'm going to show you not only how to recover your password, but how this application stores your files. To begin, I have prepared an 8gb flash drive and have created a 65mb secure section to store files. I used the provided agent.exe, which was placed on the drive, to access the secure section with my specified password. I placed a simple text file named SecretStuff.txt in this section to be encrypted.

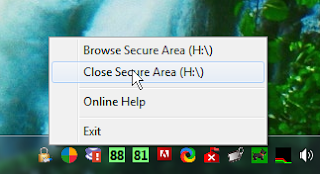

Afterwards, I followed the manufacturer's guidelines to correctly close this "secure area".

After this, most consumers would be under the belief that their files have been securely encrypted. Let's dive a little deeper and take a look at how this is simply not the case.

NTFS Alternate Data Streams

Alternate Data Streams(ADS for short) is a file attribute in the NTFS file system that was originally created for compatibility with the Macitosh file system. It allows for the use of more than one stream of data, which enables you to essentially store multiple files in a single record. This is a feature not commonly needed today. Because of this, most file viewers, including Windows Explorer, do not include a method for reading these files. This has enabled this tool as well as many strains of malware to exploit this to effectively hide files on a particular drive or partition, completely unbeknownst to the user. With this knowledge, we can use a special tool from Nirsoft called AlternateStreamView to views these streams/files. Let's take a look at our flash drive and see.It appears to have located several files with this attribute. While most of the files appear to be libraries used by the Agent.exe program, the most interesting file appears to be the data.img file which is approximately the 65mb size that I specified for secure storage. Let's use this tool to extract this file and take a closer look at it in a hex editor.

After opening the extracted file in HxD, I immediately saw my chosen password stored in plain text near the beginning of the file:

After scrolling down a bit, I noticed the start of an NTFS file system at offset 0x800. The system appears to run the full remaining length of the file.

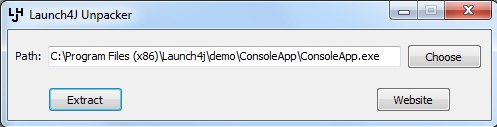

Knowing this, we can simply delete the first 0x800 bytes and save the output so that it can be opened in an appropriate viewer.

My viewer of choice for this is 7-zip. After opening this, I immediately see my file "SecretStuff.txt". Upon extraction and opening, it becomes clear that this file is not encrypted.

This is proof that all the claims by Wondershare and Gilisoft that this product employs encryption are completely false. This is false advertising and completely deceitful to their customers who have chosen this product because they believed it was secure. I hope that this article has helped to expose these fraudulent claims and helps you make a more enlightened decision when choosing your security products. Until next time, happy reversing.